How does it work?

What makes it tick?

What are the mechanisms driving gameplay forward? Are we on a railroad or in a sandbox? These are the questions that plague me when I look at the vast unchiseled form of this game. I understand on a broad level how I want the game to feel, but I need to establish more structure if I want the engine to keep running.

I hate sandbox play because it’s usually an excuse for a GM who would really rather write a book to do a bunch of worldbuilding. Worse still: if you don’t like worldbuilding, then putting together a sandbox is a chore where most of your effort goes unrewarded. No matter what direction your players engage, the other 359 degrees of preparation have become wasted.

The classical idea of a railroad is equally bad for different reasons. By removing all agency from players and presenting one scenario after another in linear fashion, you cut against the grain of what makes tabletop roleplaying compelling. Despite the fact that you are able to dedicate all your time and attention to making these scenarios, you prevent self-expression and evolve into a board game with a side of improv.

These are two ends of a spectrum that I seek to find a more nuanced approach upon.

OSR games pursue solutions closer to “sandbox” with hexcrawls and pointcrawls. Their games are very simulationist and they champion the idea that solutions shouldn’t be found on the character sheet. By contrast, “storygames” evolved from open-ended fronts in Apocalypse World into very railroad-esque gameplay loops with Blades In The Dark and its derivatives. Players have clearly separated missions and downtime phases, each with unique rules for how they begin and end or how long they last. Given the choice between the two, I prefer the discrete phases of FitD missions due to the easier ability to prep for them.

That said, my favorite approach is the quest board.

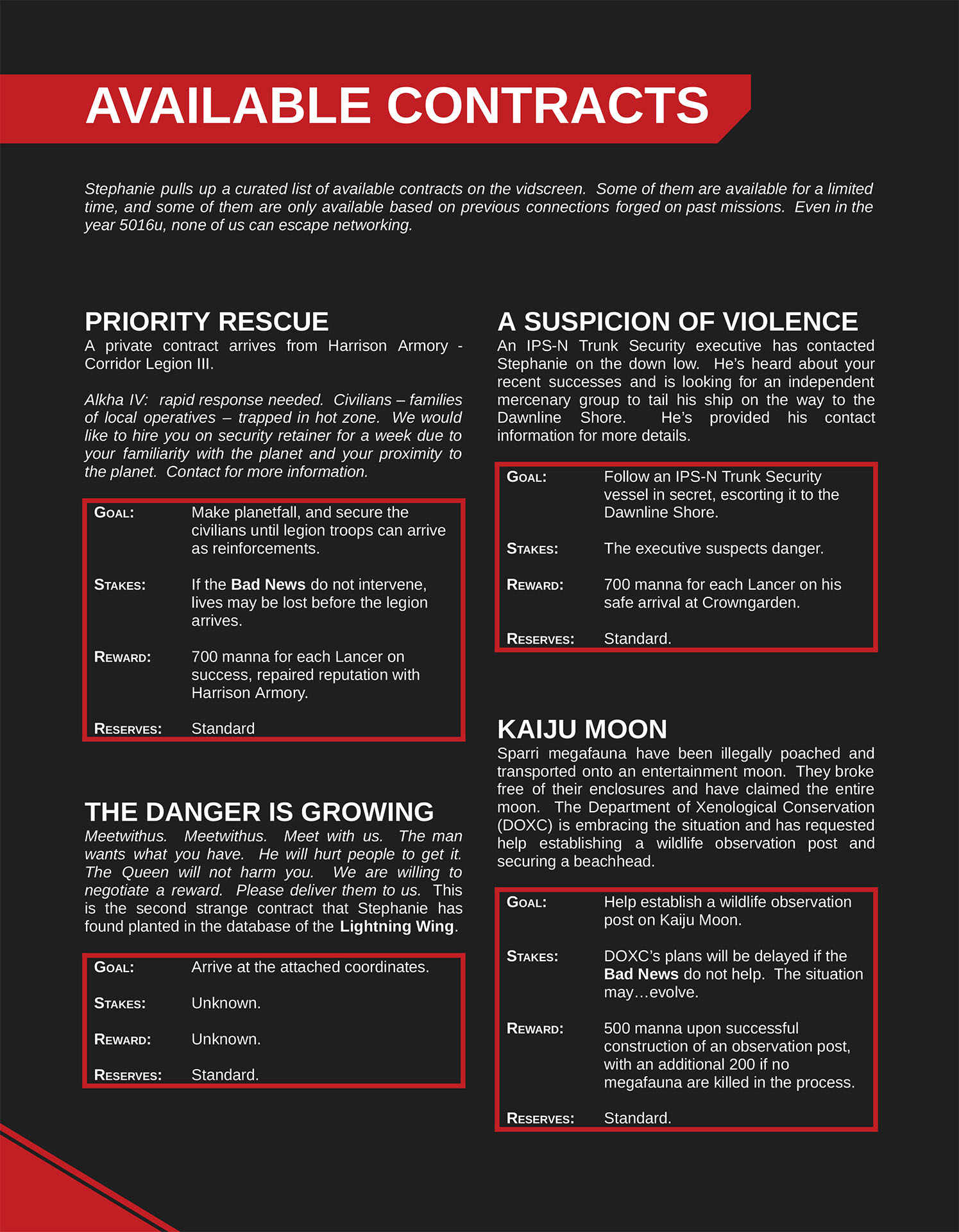

I love quests. I love giving quests, I love receiving quests. Quests are clearly defined short term goals with a record of progress and (often) actionable next steps to take. The existence of a quest board in game provides the flexibility for players to do some sandbox play if desired, but with the safety of a fallback for clear direction. The Serket Hack formalizes this system by establishing quests as the primary meta game loop.

The word “meta” does a lot of heavylifting in that sentence: quests are presented to players, not characters. Players can accept multiple quests at the same time and pursue them in the order they desire. They can also create new quests for themselves by establishing a clear (and achievable goal) through conversation with the GM. The rewards and stakes for the quest might not necessarily be clear to players up front, but each quest should have one or both. Players should gain something meaningful from each quest they undertake, or otherwise prevent something bad from happening. (I anticipate interaction with factions in a campaign setting.)

A clear goal, with stakes and rewards. When I ran my game of Lancer, I called them contracts. The flexibility of sandbox play with infinitely less prepwork.