On January 1st, Idle Cartulary over at Playful Void threw down the gauntlet by challenging everyone to make a dungeon zine. Everyone should make a dungeon, at least once. Everyone should get in touch with the hands-on craft of something physical like a zine. Everyone should get a little messy with it. I took this as a pseudo-resolution: if I make nothing else this year, I’m going to make a fucking zungeon.

The prospect is daunting. I know the purpose of The Zungeon Manifesto is to demystify dungeons, but when I stand back and start looking at the sheer scope of academic study devoted to dungeons, I get overwhelmed. Who am I to speak on what dungeons are? People have been making and talking about dungeons since the inception of the hobby. I’ll do my best to live up to the legacy.

Let’s start at the broadest possible lens: a dungeon can be anything.

Dungeons are dream sequences, time loops, cyberpunk nightclubs, riverboat chases, and floating islands. It’s usually a location, or otherwise a sequence of experiences with some method of constraining players inside. It’s not dissimilar to a “mission”, though missions are denoted by having specific objectives. That said, when people talk about dungeons, they’re usually thinking about the classic fantasy underground maze filled with monsters, traps, puzzles, and loot.

Johnn Four designs five “room” dungeons like a classic narrative with rising tension and climax. There is no regard for physical location.

Emmy Verte defines dungeons as “any location you can explore procedurally.”

One of my favorite comprehensive analysis of dungeons, The Underground Maze or Primordial Stack by Gus L., similarly defines a Dungeon Crawl as “the procedural exploration of a fantastic space”.

I am not totally convinced that “location” or “space” are appropriate words to use in the definition, but I also don’t have better substitutes. What I am convinced is that dungeons always involve the unknown. A mission and a dungeon can look very similar in practice, but a dungeon is set apart because it involves the act of discovery.

Mythic Underworld vs. Thracian Ruin

The two primary design patterns for dungeons are Mythic Underworlds and “Thracian Ruins“.

Jason Cone originated the concept of the Mythic Underworld in his supplement Philotomy’s Musings. The primary idea is that the Mythic Underworld exists for the players, regardless of whether or not the dungeon “makes sense”. Mythic Underworlds are generally large and sprawling, with untold levels extending downward — each more dangerous than the last. Cone’s approach to dungeon generation is to improvise it with the players, providing them options and building the maps in the directions they choose to explore.

Thracian Ruin refers to an OD&D supplement called The Caverns of Thracia, written by Jennell Jaquays. Jaquays designed levels in antithesis to the Mythic Underworld-style, creating dungeons with purpose behind their layout. If monsters are present in the dungeon, there needs to be a reason for them. Moreover, the dungeon must have rooms for them to sleep and eat. The Caverns of Thracia included multiple factions with detailed descriptions of how they interacted with one another. The space was intricately mapped out and filled with secret passageways and looping corridors: all in service of the idea that living people needed to be able to walk around the dungeon in ways that made sense.

Neither of these approaches are necessarily better than the other, but it’s important to understand how we design a dungeon before we begin. I favor the Thracian Ruin approach: I like my dungeons to “make sense” and connect to broader expectations of the worldbuilding with internal consistency.

So how do we build one?

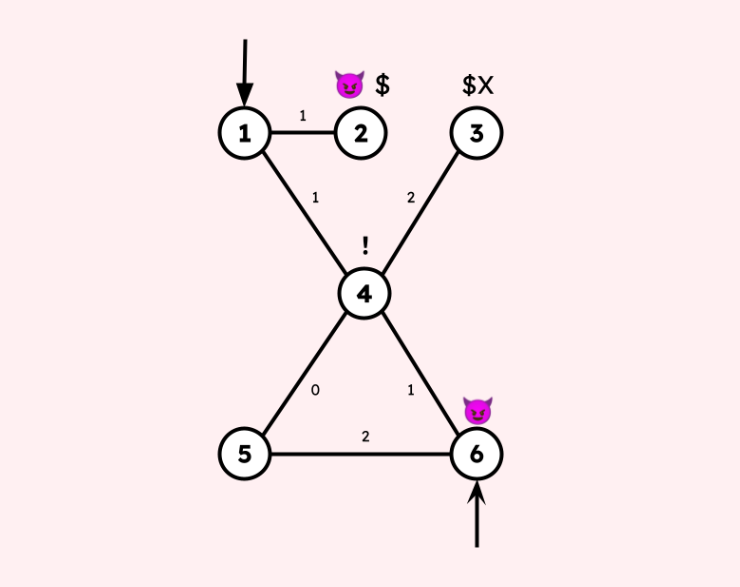

I like graph theory. It’s what I had to learn in college for computer science and it makes sense. Nodes are connected by edges. Marcia B. has an excellent article for generating six-room dungeons from the perspective of a node graph.

(original diagram by Marcia B. in the above linked blog post)

Mapping a dungeon as a node graph appeals to me because I’m not particularly interested in playing games based around the 5-foot square or what happens in the hallway. As Marcia suggests, the edges of the graph are either normal doors and hallways or they are longer distances which can be represented by flux space (a topic for another day). Either way, the connections themselves are not points of interest (if they were, we would represent them as a node).

The Serket Hack

I’m going to be building my zungeon for The Serket Hack, which is wildly different from the constraints of OD&D that we’ve been looking at.

First: the broad setting of TSH has similarities to a Mythic Underworld, being shaped around the players and having different natural laws than the real world. However, individual locations can still be designed Thracian Ruins-style with unchanging maps and respect to the residents.

Second: in The Serket Hack, the word dungeon means something specific. A dungeon is a place with prisoners. If the players are not the prisoners themselves, then their purpose is freeing the prisoners. There is no treasure to be found in a dungeon, though players may find useful items. If players seek wealth, then they should be breaking into vaults instead of dungeons.

Third: the people of the echolands are exploited as a resource in a very literal way. A human soul, kept trapped, can serve as a powerful catalyst for magic. It is common for a group of bandits to kidnap people and use them to generate wealth. Admittedly, I still need to sketch out the details for this aspect of my worldbuilding. The main point is that there’s a reason for dungeons to exist across the echolands and motivation for the forces of evil to build them, whether it’s a gang trying to get rich quick or a cult fueling unholy spellworks.

The Pitch

In the midst of a gang war between fighters and mages, you have to break into the fighter base and liberate recent captives before either side wins and moves the prisoners to a more secure dungeon.

The fighters have a hideout in a mid-sized city. There’s a warehouse, a watchtower, and a connected complex of living spaces. The mages fly on hoverboards and operate like a biker gang. The two gangs used to work together but the two leaders had a messy breakup recently and this is retaliation. Both sides suck.

I’m really excited to work on this more and get something physical into my hands.